May

10

2025

WHAT MAKES ME CRY

I often cry when I watch parades, particularly when I watch marching bands. How does such a diverse group of individuals come together to play music while marching down the street, often clad in identical, uncomfortable uniforms? It is a feat of coordination, memory, and consistent rhythm. They are committed to the whole. Their individual contributions are crucial. They share the moment with each other so flawlessly that we become part of it too.

This experience reminds me of home, which is filled with countless items: photos, furniture, old letters, books, tables, and chairs—everything that transforms a house into someone's home. When one of these elements is removed, it fails to capture the essence of that home on its own. It becomes isolated, diminishing in significance. Just like a marching band, a home is built from many components that must coexist to evoke powerful emotions and a recognition of a singular identity.

Occasionally, I come across displays in stores of large collections. Recently I saw one featuring an array of beautiful ceramic bowls in various colors. I found myself wanting to take the entire collection, as a single bowl felt lost and empty without the others.

We had 25 minutes to pack our home and evacuate. A wildfire seemed to appear out of nowhere. Flames were moving fast from the canyon close by. We could see a glow over the trees, just past our neighbors yard. I grabbed hard drives and photo albums. Then I found myself standing in the middle of my home, in the middle of my living room frozen. I didn't know what to take. Everything seemed equal. Everything seem to work together as one thing. I felt like I had to make a choice and I couldn't figure out how to make my life fragmented in a split second.

So, I carelessly tossed dirty laundry in with my clean clothes to fill the suitcase, neglecting beloved clothing, cherished books, and artwork adorning the walls. I packed what felt necessary in that frantic moment: notebooks for teaching and current classes, forgetting the notebooks filled with inspiration—those from my college days studying dance with Betty Walberg, and choreography notes and ideas collected over the past 30 years that still resonate deeply.

Now, we are grappling with the ramifications of starting anew—collecting, creating, and marching in the parade of a life that has suddenly transformed. As I look around the house we plan to call home for the next few years, it feels more like an Airbnb than a place of belonging. Excitement coexists with regret and mourning. I am left waiting and hoping for that familiar feeling I get when I watch a parade. Will it return the second time around?

May 21, 2025

PING PONG BALLS

On one of the first nights after the fire, I thought about the giant bag of ping pong balls left in the closet. A kid who came to one of Nuala’s birthday parties, played a little too hard and fast in the backyard and lost most of our balls. He felt bad and ordered a bag of at least 100 of them. When they arrived we had already gotten rid of the ping pong table. So, I stored them in the closet. Did they melt when the fire hit or did they pop as the air was sucked out of them.

These balls meant nothing to me but they appear in my mind and they reappear when I find myself remembering things we lost in the fire. I have a very clear image of small white balls in a plastic bag on the top shelf of our hall closet. A bag I no longer needed, and I see them almost every day. Perfect white round shapes, that reminded me of the eccentric items we all store somewhere.

Some people listen when we retell the story of leaving our home with just a car full of belongings, others seem to be listening but turn the conversation toward them. Sharing stories they think are the same as losing almost everything you own. It’s not the same. It’s not even the same between those of us who have all experienced this.

I want to walk by the framed photo of my mother as a toddler sitting next to her twin sister. The picture where she looks most like my daughter. I want to be reminded of my sister’s engagement party on a hot day in a park which ended in a water fight. Paul captured her at a moment of exhaustion, looking at the camera, her shirt and hair dripping. The one painting from Gene that we hung in Nuala’s room even though it was too big and took up the entire wall. I loved it. And how odd that so many visitors never even noticed it. Mike’s painting I bought for Paul. A man standing on the corner of a sidewalk with his hands raised as if he was in the middle of performing one of my dance phrases.

I want to know what happens when a refrigerator burns, a bed, my shoes, all the VHS tapes stored in a closet. The drawer in the bathroom full of hair ties and strands of hair. All the towels I folded over and over again. The full length mirror in our bedroom and Paul’s hats. What did it look like when the flames took over the photographs spread along the dresser - Nuala at the beach. The giant framed photo of a man in China picking up take out food. His face looks right at Paul’s camera, he leans to one side and his bike leans agains the building. A bike that looks as if it barely stays in tact with wire and rope. No longer will my friend, April, ask me how I sleep in a room with a man like that looking at me.

People tell me their stories thinking they know. How could anyone know until it happens.

June 10, 2025

TREE CEMETERY

The trees that died by fire or were on their way to death were cut down and tagged, leaving the stumps on our empty lot.

It was mostly quiet when I noticed how many there were. We were both immersed in our thoughts.

Paul was putting up a "No Trespassing" sign before moving on to the relentless task of cutting back the bamboo. So many trees and fences had been destroyed, leaving gaps between our yards. That's when I saw Ramon and his seven-year-old daughter pull up to their empty lot behind ours.

They had a remote control car that they drove around on the foundation where their house used to be. I waved to Ramon and he waved back. There was nothing more for us to do, but just sit there wondering what really happened to us, to our neighborhood, to our lives. Maybe he was doing what I was doing remembering what was exactly there. Maybe we both needed to return and reconnect with the space, even mourn a little bit. But it did feel nice to watch his daughter having fun in a place that looked destroyed to both of us.

I counted the trees, I took a picture of each tree grave and I said goodbye.

_______________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________

June 21, 2025

PATIENCE

Things Shouldn’t Be So Hard by Kay Ryan

A life should leave

deep tracks:

ruts where she

went out and back

to get the mail

or move the hose

around the yard;

where she used to

stand before the sink,

a worn-out place;

beneath her hand

the china knobs

rubbed down to

white pastilles;

the switch she

used to feel for

in the dark

almost erased.

Her things should

keep her marks.

The passage

of a life should show;

it should abrade.

And when life stops,

a certain space—

however small —

should be left scarred

by the grand and

damaging parade.

Things shouldn’t

be so hard.

How is it so effortless for people to navigate the world oblivious to how difficult it is for others? They don’t see that your mother has just passed away, that you are battling a terminal illness, or that everything you possessed has been destroyed. At times, you feel the urge to stand on a hill and shout, “Do you know what just happened to me? Do you realize how hard this is?” But you restrain yourself, knowing that everyone would rush up that hill to share their own burdens. The overwhelming cacophony of all that suffering would be too much to bear.

Still, I wish we all had more imagination and curiosity to understand how others cope. The echoes of such events never truly fade; we are marked, scarred, and forever changed. I often find myself wishing I could simply move on, that this new life I’m leading could erase the memories of the past. Sometimes it does, but I cannot deny how my experiences have shaped me. My home, my belongings, and the everyday habits I developed in the place I lived longer than anywhere else have all contributed to my sense of self in ways that only loss can illuminate.

I miss seeing the titles of the books on my shelf, even those I hadn’t revisited in years. They were reminders of how to think, how different characters and authors engaged with the world. I cherished all of Iris Murdoch’s novels because my mother once worked in a bookstore and was able to send me each one until I had the complete collection. She even sent me Edward Tufte’s books—not because I asked for them, but because I mentioned him in a conversation, and she recognized the titles when she saw them in the store. I remember my numerous art books on artists like Joan Mitchell, one of my all-time favorites, as well as Hilma af Klint, Douglas Dubois, Yvonne Rainer, Marlene Dumas, Jennifer Packer, and poetry collections by Atsuro Riley and Kay Ryan. I had all of A.S. Byatt’s novels. Being reminded of these artists every day was a gift I took for granted; it enriched my life not just through physical things, but by inspiring me to think more deeply, question, create, and imagine.

This grief process seems to resist simple understanding. I don’t expect others to comprehend my struggles while I am still grappling with confusion myself. Therefore, I extend patience and compassion to those who cannot see how challenging this continues to be. I am skilled at compartmentalizing, managing my responsibilities, and maintaining control. Maybe now is the time to ease off on that instinct and allow a little more patience and compassion for myself.

July 14, 2025

WHEN WILL I EVER REALLY SLEEP AGAIN?

I woke up at 3:30 AM, thinking about the photographs of my younger self that I will never see again. A dog barked in the distance, too close to ignore. I felt a sense of sadness knowing that I may not be remembered like someone famous, which is ridiculous and embarrassing to think is important. There’s no evidence that I was once a young person or an artist.

I remembered the emails K and I exchanged, printed out and saved. My notebooks filled with handwritten notes. The photos from our first trip to Europe—the Polaroids I took every day and awkwardly taped into notebooks with captions that didn’t add much—are all gone now. Some memories remain in my mind, but they feel heavier as time passes.

I had written a letter for P and N to open only if I died unexpectedly. That’s lost too, likely too dramatic for its own good.

I put earplugs in my ears, feeling hot then cold. My hip hurt, and I couldn’t decide which side to sleep on. I wished I could sleep on my back, but snoring and leg aches kept me awake. I set the alarm for 6 AM, realizing it was only 3:45. I could easily oversleep before class at 9.

There’s so little of my past that a historian might find. But why does that matter? Is it just a fantasy of mine?

August 4, 2025

PHOTO RECOLLECTION

I came back from New York with a small stack of photos my sister Lizzie gave me. Many were ones I used to have, and it felt good to see them again, to hold them. I also brought home an old leather pouch, so worn it left behind a trail of orange-yellow dust on everything it touched. Inside were letters, and funeral receipts from the 1920s and 30s—never more than $250 total. That included the casket, embalming, chairs for the wake, and the burial.

The letters were hard to decipher. Everyone seemed to be named Margaret, Daniel, or Michael. Eventually, I realized they told the story of my grandfather going to live with his mother’s sister after his parents died. There were also details about debts and late rent payments. Her name was Mary Spalding—a name no one in the family recognized. Not my 89-year-old aunt or her 79-year-old cousin. From what I could piece together, she took my grandfather in and raised him. And then, somehow, she was forgotten.

I pinned some of the photos to my new bulletin board. Then I got irritated—almost angry—that I don’t have photos like that anymore. Not the kind you tack up. I have albums, sure, but they stay closed. The loose envelopes of photos I used to keep are gone. The ones with pinholes in the corners, some with rust marks from old thumbtacks. Others had a thin layer of grease from years on the fridge. Curled at the edges.

There’s one of Nuala holding a teddy bear—a Polaroid. She looks like she’s from another time entirely. Her face is serious, almost scared, sorrowful. I always felt better knowing that the little girl in that photo had that bear to cling to.

I used to hate that the photos on the fridge were greasy, that some had food stains. Now I miss them. There was a blurry shot of David sitting in our kitchen in San Francisco. I loved that photo, even though I knew he wished he were back in New York, not in my kitchen.

There’s one of Wesley, our white Siamese cat who never meowed—until Bob, the black cat we also lived with, died. After that, he never stopped. Someone took a picture of Wesley perched on my back while I was on all fours in the living room. I’m in a white sweatshirt and jeans. He looks majestic, like royalty on a throne. I’m the servant, the steed. We left him with a friend when we moved to Los Angeles. She took good care of him.

Photos. They are so mysterious. And so misleading.

August 19, 2025

FLEA MARKET FIND

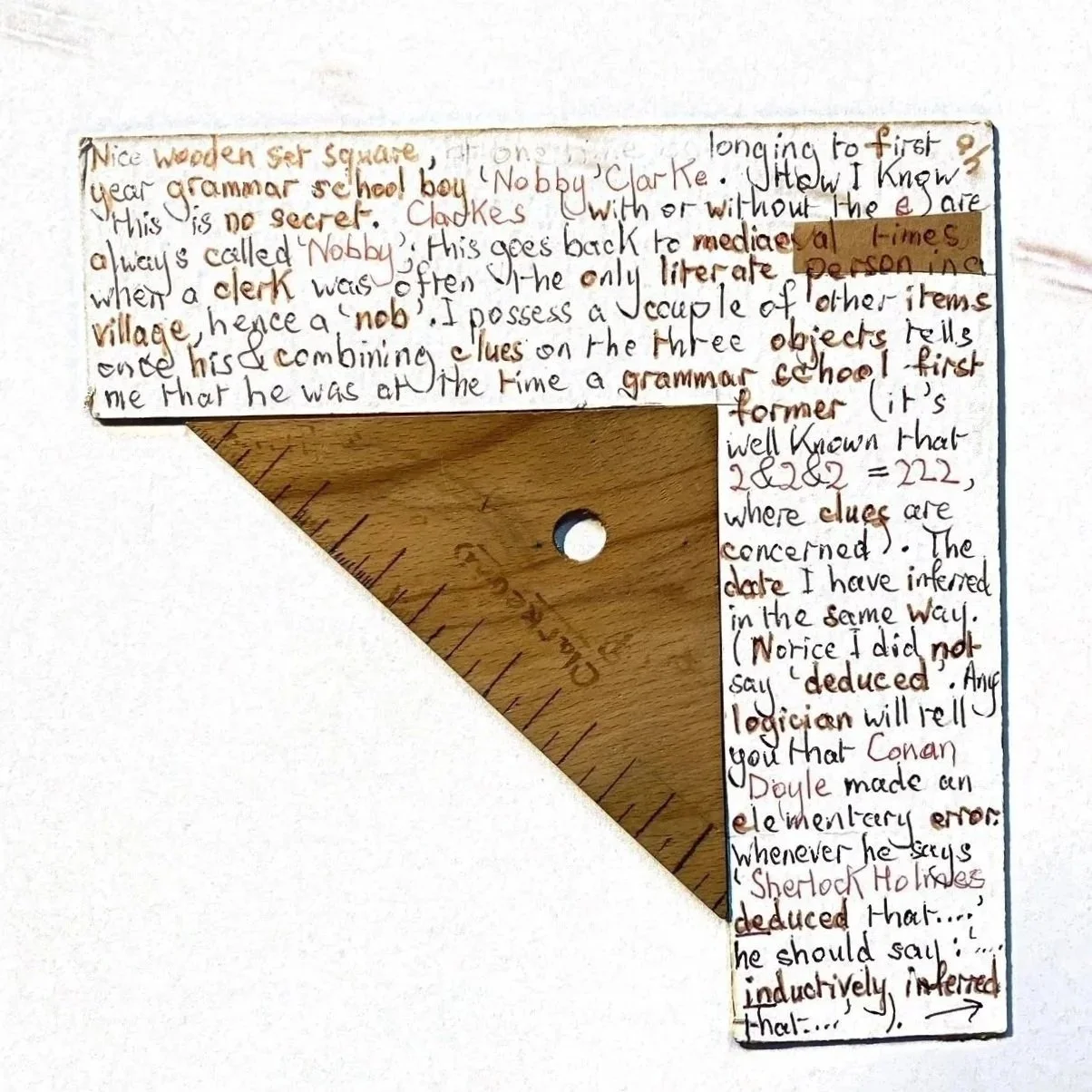

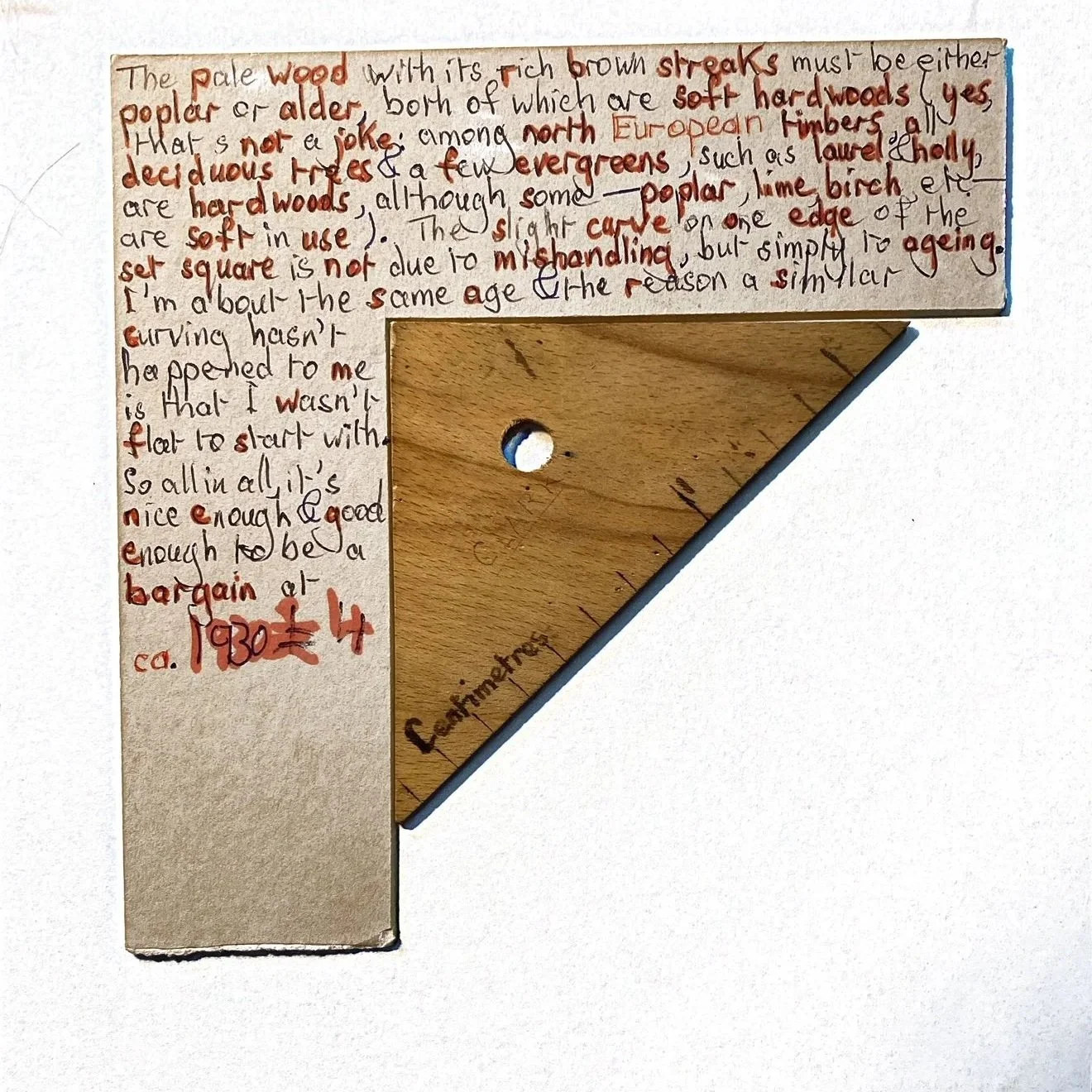

I’ve been planning my courses for the Fall semester, including a Documentary Storytelling class I only get to teach every other year. One of the assignments explores how objects can hold hidden histories and private narratives. While reviewing the assignment, I came across photos of a wooden set square I bought at a London flea market years ago.

The stall owner, a wiry, elfin man with a constant grin and knee pads strapped over his pants, as if always ready to scavenge, attached a story to every object he sold. The set square’s tale was written on a piece of white cardboard and tied to it. I spent nearly two hours at his tiny, cramped stall, reading his notes about record album sleeves (not covers, just sleeves), rusted metal containers from the Thames, and other odd scraps that looked more like trash than treasure. But his stories transformed them—filled with history, fragments of his childhood, digressions both obscure and funny.

His writing was never consistent—different pens, shifting colors, words traced and retraced. I still wonder if he was embedding some kind of puzzle or secret message in those choices.

Finding the photos made me happy and sad. I was sad because the original objects and writings are gone, but happy because I had forgotten that I had taken pictures of all of them. The set square has the layered history of the tool itself, the man who found it and wrote about it, and then me who stumbled upon it at a flea market and carried it home. Now my students will see it as part of an assignment about the many ways stories live inside objects.

Objects are never just things.

September 7, 2025

ADMISSION

I never know when or how to tell people that my house burned down. Often, I’m in the middle of a conversation, and it feels like I have to mention it—or else I’m lying. Or perhaps it’s not lying exactly, but leaving out an essential layer beneath the story, the anecdote, or the explanation I’m offering.

As soon as the words leave my mouth, I catch their expressions, and all I want is to take them back. Instead, I fumble, trying awkwardly to soothe their inability to respond, muttering something like, “It’s life,” while my body is frantically wanting to spill everything.

Sometimes, the person I’ve just told moves closer, curious for details—wanting to know what it felt like. In those rare moments, I have their full attention, and I tell them. Some even want more, almost as if they are placing themselves in my shoes.

But most of the time, it doesn’t come up. My responsibilities, classes, and commitments overshadow the event and the lingering trauma. I get no breaks—or maybe I simply don’t allow myself to ask for them.

September 15, 2025

A CHANCE ENCOUNTER WITH A MARIACHI BAND

He introduced us as “casualties” of the fire. The word struck me as strange — I’ve always associated it with war, with loss of life, not with us standing there alive. At the same time, it seemed fitting. He had just met me and needed a quick way to explain to his co-worker what had happened. Long ago, the word once meant accident, mishap, or chance event — even chance encounter — before it became tied so heavily to war. In that sense, we are casualties. The fire was a random, accidental event. Not fate, not the universe sending a message or issuing a test. Just a chance occurrence that changed so much — and, oddly, not all that much.

I still work at the same job. I live not far from where my old home once stood. I shop at the same stores, or their near-identical franchises. I still feel the same small irritations when the heat wave drags on, or when someone leaves their car parked in front of my house for days. When we run out of milk for coffee. My clothes have been replaced, and I even own a stapler and scotch tape again.

A woman at work once said, “This is going to be something you’ll be processing for the rest of your life.” I hadn’t expected that from her, and the weight of her words stayed with me. She said it with a kind of knowing — experience, maybe — that I’ll never fully understand. It’s strange how someone you aren’t especially close to can suddenly put everything in perspective.

Our new house has no front yard. At night the streetlight pours straight into our bedroom. Only a stucco wall separates us from the road, and I often feel exposed. Except for one morning — a Sunday at 7 a.m. — when a live mariachi band appeared across the street, serenading our neighbor for her birthday. They played for an hour and they were really good. We stayed in bed and just listened wondering how we would tell this story.

October 4, 2025

NOT WHAT IT FELT LIKE, BUT WHERE

She told us she was eighty-two. She looked younger than me. I noticed the cross on her necklace as she spoke about the spirit. She was clergy. When she turned seventy-five, she said, she had looked in the mirror and wondered where all the time had gone. Maybe that was when she decided to speak to people the way she did with us—certain that there is a God, that we each have gifts, and that our task is to recognize them. She was kind, and she was grateful for what we brought into the space.

But does the same “gift” mean the same thing in another culture, another time, another place? What does it mean when your photographs or paintings are valued and understood in one era but not in another? I don’t think of it as a gift inside us. I think of it as a kind of attention—a recognition, an awareness of how our work resonates. Where does that resonance lead us? What does it ask us to question or to see differently? Could that kind of attention itself be called an inherent gift? I’m not sure.

When I teach, I hope to help students strengthen their attention. Maybe I just assume that attention lives in all of us and can be nurtured. I think it needs stretching—a kind of yoga for perception. Or maybe attention wakes up when we’re confronted by difficulty. Sometimes it shuts down instead. But for me, it feels like a shift in the lens.

The aperture opens wide, and the view becomes overwhelming. Yet I am in control of the depth of field. I choose when to bring everything into focus—or only a single part.

And then there are the books. I keep thinking about them, lined up in what used to be my living room. I still remember the spines, the authors’ names, even the books I never read. They remind me of other lives, other perspectives, other voices. I still remember reading that line in The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell: “I lost my virginity in Syria.” Not what it felt like—but where. Syria.

November 2, 2025

A GIFT FROM ROMAN

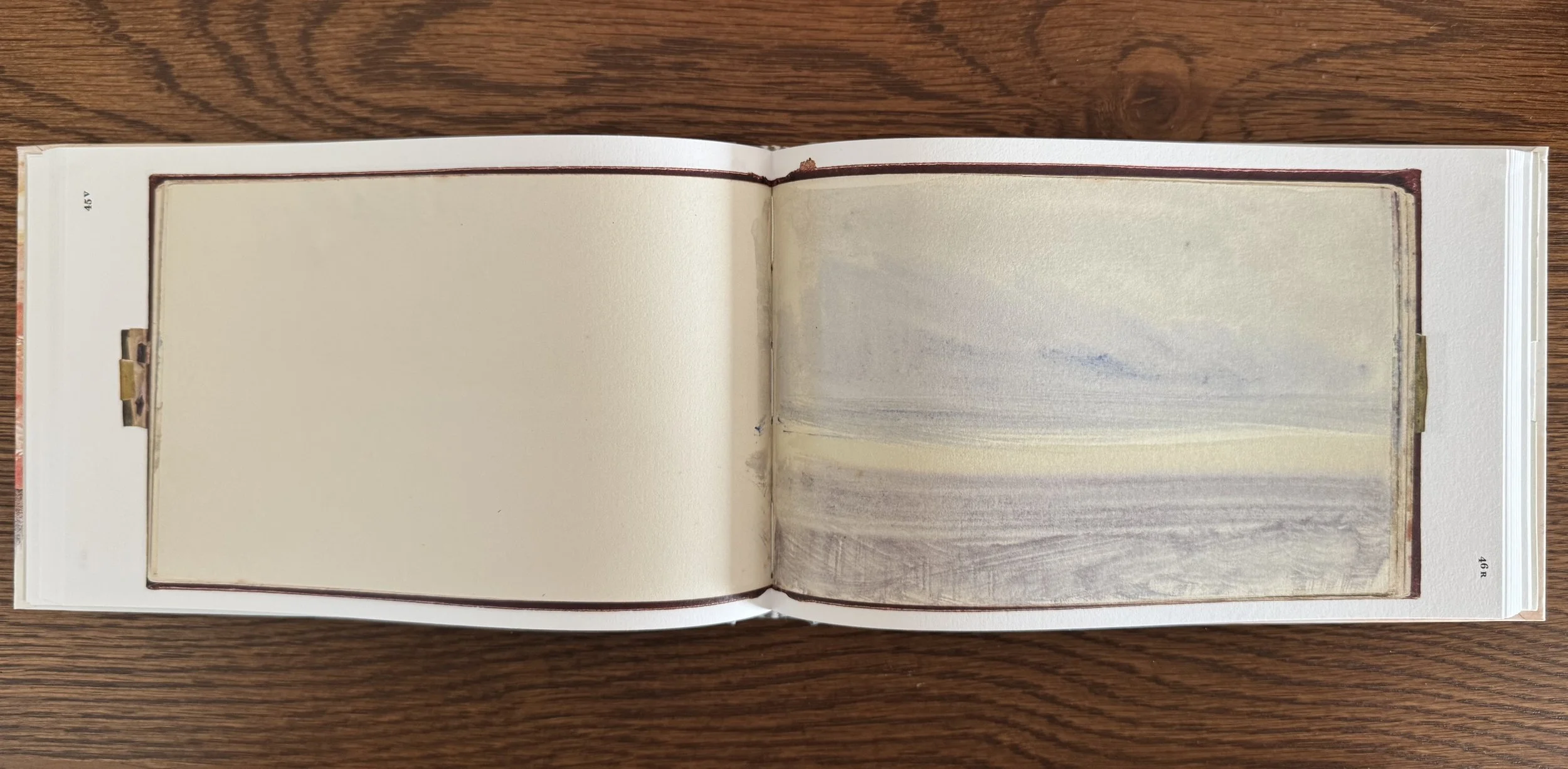

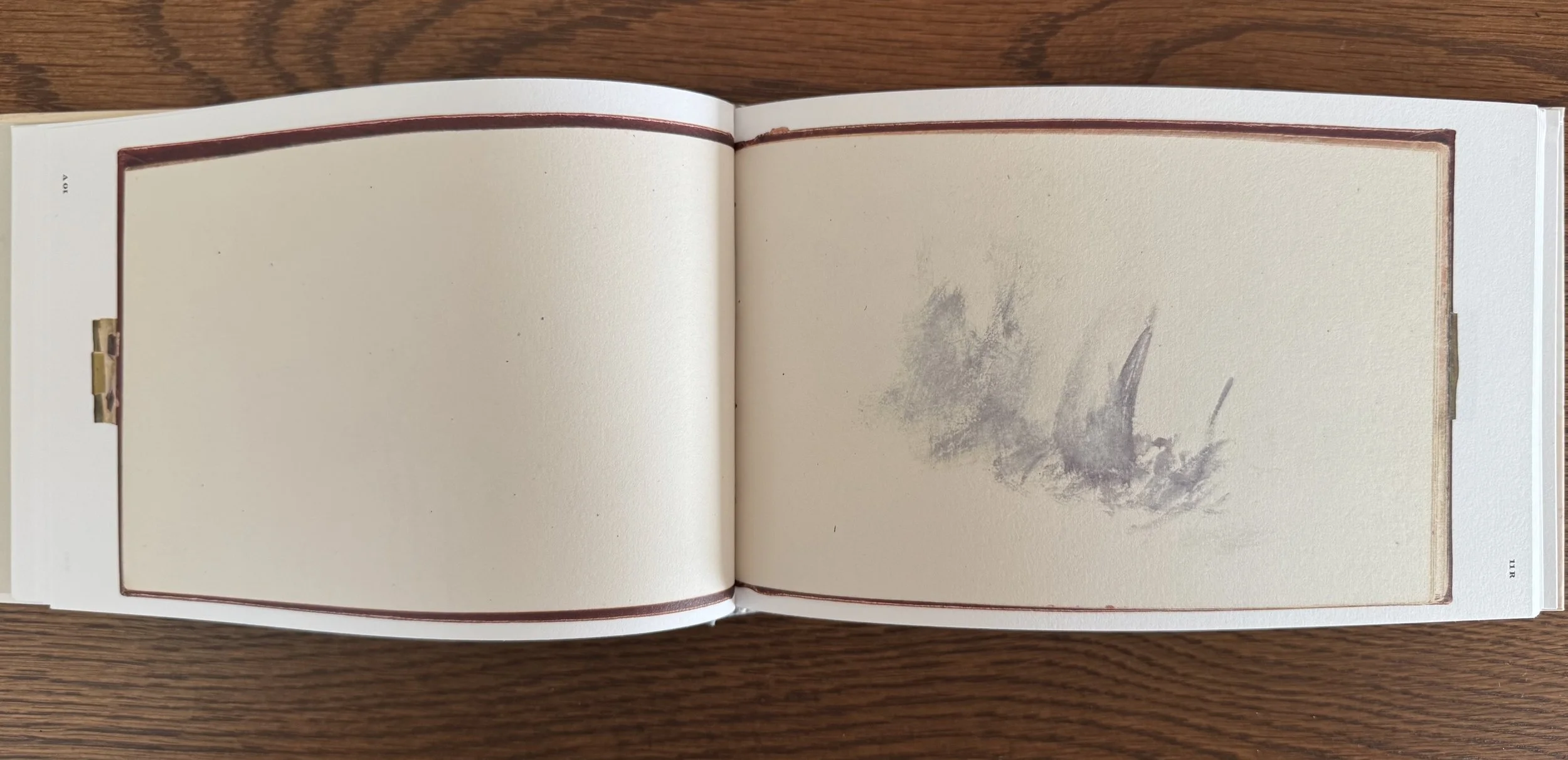

I have a new book — Turner’s last sketchbook. One of more than 300 he made. It’s small, filled with watercolor sketches: simple washes of muted color, often just a hint of a horizon. If you didn’t know they were his—or even if you did—you might find them unremarkable. Yet they are astonishingly beautiful.

You look at them knowing they were made at the end of a lifetime spent painting, observing, and noticing what most of us overlook. A pale gray stroke near the top of a page and a darker gray shape below it—perhaps a ship, or a figure, or fog swallowing the sea.

The sketches hold a mystery and a quiet familiarity that only come from an artist who has spent a lifetime translating the world. They carry the confidence of a single gesture, or perhaps something even rarer—a willingness to make a mark and see where it leads.

Turner died at seventy-six. These were his final sketches. Someone might look at them and say, “Anyone could do that.” But I disagree. An artist near the end of life paints with a memory-filled hand. A few strokes of color that suggest sea and storm are enough. The life lived, the years of looking, the imagination—all collaborate in those gestures. There is no need for completion; the marks themselves contain the story, the experience, the memory.

When C and I were in Paris, we stumbled upon the Picasso Museum. One room was lined with all of his final drawings. They looked like quick squiggly lines but at closer inspection, they were actually portraits. Some may have mistaken them for a child’s drawings. I found them deeply emotional and moving. They seemed urgent as if he was trying to capture everything before his time ran out. There was the weight of a lifetime of looking and seeing, the simple squiggly lines asking me to finish it, to write the rest of it. The rest of the story for me and him.

I think of our old home, now gone. Did I live there long enough to carry its history within me? Did those years—raising our daughter, teaching, making and losing friends, saying goodbye to parents, and finally losing the house itself—become part of who I am? Will I someday make a mark on a paper, just a single gesture that holds all of it? All the things I remember about the house, the light throughout the rooms, and all the different people that lived in that house before me?

• Thank you Roman for understanding how important it is to get books back in my life.

November 15, 2025

ROO

I hear the cat moving through the house. Downstairs, eating her kibble, each bite sounds like the rattle of plastic beads. Then upstairs, scraping endlessly through the litter, rhythmic and insistent, as if she’s mapping the rooms with sound. Her habits create a map of the house, giving shape to the space we live in.

At night she presses so close to me that there’s barely room to turn. The bed feels smaller now, crowded with her, with P, with me.

When the fire came fast, trying to get her out felt impossible. She’s old, stubborn, firmly set in her ways. I wasn’t sure we could do it. I even wondered, with a kind of terrible dread, whether we’d be able to get out at all if she resisted. Would we have to run and leave her behind? The thought still haunts me. We wrapped her in a towel and managed to squeeze her into the tiny crate we hadn’t used since she was a kitten. Somehow it worked. We did it again and again over the following days.

It changed her. She’s more dependent now, more vocal. Still cranky, still old, still unfriendly, but she needs us. Her meow is grating, and the new wheezing and sneezing make her sound like she’s about to throw up. We rush toward her every time, ready to drag her off the carpet before she throws up. Most of the time nothing comes. Still, we listen for her noises. We watch.

I know I’ll be heartbroken when she’s gone. Even though her voice grinds on me, even though she steals half the bed. We love the complicated ones, the difficult ones. Maybe because loving them requires effort.

December 2, 2025

THE DISASTER TOUR

I’ve been back to the site three times in the past few weeks. We take people on what we’ve started calling “The Disaster Tour.” P describes how the fire fed on the houses, how the west side of Altadena suffered more damage, how someone had an old Craftsman house moved onto their lot, and how others are living in RVs where their homes once stood. Most of the debris is gone now. We even see the first signs of rebuilding—new construction rising beside for sale signs on empty lots.

It rained recently, and everything is suddenly green. There’s even mud and puddles scattered around. Acacia has taken over our lot—plants we never had before. It’s beautiful, though it makes P sneeze endlessly. The views stretch so far into the distance that I often wonder if I’m seeing the ocean, though I know it’s too far from here.

I met a friend on the lot, and we talked about using the space as an installation. It felt like a beginning, enough to make me feel motivated again. I drove home alone, taking a slightly different route, and this time the emptiness was unmistakable—the absence of people, houses, structures. And yet the openness was striking too. No obstructions, just a horizon that felt impossibly far away. The devastation and the sense of possibility seemed to blend together, shifting from the intimate to the vast and back again.

That’s why, whenever I visit the site, I end up at the swing, filming—hoping it will still be there each time I come back.

December 13, 2025

DEAD ROSES CAN BE BEAUTIFUL

Across the street, our neighbors have created what looks like a giant Christmas tree made of lights. At night it gives the illusion of a single towering tree, but in daylight you can see the truth: a large pine, a palm tree at its base, and strands of lights running through the front-yard bushes and spilling over the wall that surrounds the house. It’s so bright it would flood our bedroom if we didn’t have blackout shades. I like Christmas lights. I usually enjoy the rituals and festivities of the season. This year, though, it all feels lackluster.

I remember that all of our Christmas ornaments are gone. I find myself moving through the garage, where we once stored so much, and the list of what burned keeps growing. All the DVDs and tote bags for my film, Lost In Living. Not that anyone watches DVDs anymore. And I never actually enjoyed putting up Christmas decorations, especially taking them down. I feel both sad and relieved. The weight of useless DVDs, the obligation of decorating a tree, finished, done. And yet, there were ornaments I liked seeing once a year: the flimsy paper ones Nuala made in elementary school, the miniature drum set, the wooden elves and reindeer. All gone for good.

But I don’t exactly miss them. Or maybe I miss the ritual of pulling them out once a year. How many things are like that? How many objects exist only for special occasions?

I keep going through the garage. My old portfolio of drawings from college. Some I’m happy to forget; others I want back. The drawing of dead roses drooping in a vase. I had brought the roses from home to the drawing studio and spent days working on them. The drawing was larger than life, and I was beginning to like it. Then one day I arrived and the vase and flowers were gone. Disappeared. I didn’t think anyone would have thrown them out, drawing studios were full of odd, temporary things, but I couldn’t find them anywhere. Eventually, I put the drawing away.

Months later, I attended another student’s thesis exhibition. She was a far superior painter. Her work was beautiful, lush paintings of my vase and roses. I said nothing. I loved the paintings and felt a quiet satisfaction that she had chosen to devote a series to something I, too, had found worthy of attention. Still, I wondered: did she think the vase and roses belonged to no one? Was she so taken by the still life that she had to claim it? Artistic drive overriding everything else. I don’t know. I only knew that I could never have made paintings as lovely as hers.

December 29, 2025

SOMETHING THAT IS NOT A STAR

Barn burned down—

now

I can see the moon.

—Mizuta Masahide

This poem often appears when people speak about profound loss. Much like my house burning down. The loss of so many things has stripped away how I am seen in the world and how I see myself.

Can I see the moon? Not yet. I wonder if I will disappear before I recognize it. If the ordinary motions of living will reclaim me before I can hold onto that brief understanding of how small we are in this vast universe.

The moon may appear, and I won’t be able to catch it. I imagine it flashing into view as I drive home at night, then vanishing behind tall buildings. I will be focused on the road, the glimpse allowing only a moment’s pause. Not a new perception. Not yet.

When I lived in Florida with my aunt, uncle, and their children, I felt rescued. My six siblings and I were taken in the middle of the night. Our mother was in the hospital, near death, unable to care for us. When doctors said she would survive, they warned her recovery would be long. Our father left her for another woman, lost his job, and disappeared, leaving us in deep poverty. We left quietly, telling no one, afraid he might appear and stop us. I was relieved to be going somewhere safe where there was food, electricity, and a working phone, but I was also losing my parents.

Florida is mostly flat. The sky takes over. It becomes a giant animated canvas, gray with storms, then wide and blue, then streaked with orange and red as the sun sinks. Sometimes I would lie on the impossibly green grass and stare into this canvas. The sky even filled my peripheral vision. I let it cover me. That sense of smallness was comforting. It clarified things. I felt insignificant, but not erased, more like standing in awe of forces beyond my control. Surrender felt necessary. My daily worries diminished.

Maybe that is what it will be like when I finally see the moon. The obstructions will clear, if only briefly, and something will shift. The field of view will widen. Focus will expand, and I will let myself belong to it.

Or maybe I will realize I have always belonged—

even when my home burned down.

Thank you, Audrey, for introducing me to this poem.

January 5, 2026

WHEN IS A HOME A HOME

Tonight I’m getting a glimpse of what it might feel like when P leaves for a much-needed job. He’ll be gone for four to five months. We’re in a new house, one I don’t fully live in yet. The other day, P and I were talking about our attachment to home, and we both realized that he has more of an attachment than I do.

I didn’t grow up with the sense of home as a comforting place. My early years were fairly normal, but the house belonged to my parents. My mother decided how everything should look, how things were decorated, where our belongings went, and how our clothes, books, and toys were organized. Children didn’t have much of a say back then. We accepted how our bedrooms were arranged, what hung on the walls, and we certainly weren’t allowed to mess things up.

I have a recurring dream where I’m in “my house,” discovering secret rooms one by one. The dream is always deeply satisfying. Only in the dream does my home expand to include rooms and private spaces meant just for me. There were no secret rooms in the houses I grew up in, though I often hid away in my bedroom to read, especially after convincing my mother I was cleaning. I wasn’t bothering her, and that was enough.

Now I find myself in a house I haven’t even lived in for a year. We spent just over twenty years in our home in Altadena, and I was only beginning to feel that it was truly mine. Twenty years is a long time to make a place feel like home. I remind myself of that as I move through this new space. It’s smaller, closer to the street, and it still feels as though it carries the remnants of the former owners. I sense them lingering.

How will I manage here alone? There will be plenty to do, school, friends, and family, but nights like this make the silence feel heavy and a little overwhelming.

I remind myself not to dwell on the future. The days will arrive, and I will take them as they come. Anything can happen. Nearly a year ago, we lost our house, everything in it, our neighborhood, and the lives we once knew. We now focus on living in the present, and we are fortunate that this present still has room for the past.

January 20, 2026

MISTAKEN IDENTITY

First day of classes.

I pulled the card that said mistaken identity.

I listened as the students told their stories.

Meanwhile, three stories were inside my head.

Do I talk about the identity that no longer exists because of the fire?

Or do I tell the story about being a junior in high school, mistaken for the most popular girl in school?

This was Florida. I apparently looked a lot like her—but I was not popular. I was from California, new, and a junior, so I made no friends. I also showed up wearing a backpack, which was unheard of back then. People said, What are you trying to do, climb a mountain? By the end of that year, everyone was wearing backpacks.

People thought I looked like her and would call out, Kyle, Kyle. It was strange. Here I was in a place where I knew no one, yet I looked like the person who knew everyone.

The second story was being mistaken for someone’s sister-in-law in a thrift store I loved. After hearing the same comment every time I walked through the door, I stopped going. Part of a larger pattern. I seem to have a face people think they know. I hear it all the time: You look familiar. How do I know you? I don’t know. Do I really want to investigate that? Sometimes I do. Sometimes it’s easier than having a real conversation.

My mother used to say she could only afford one face. She probably stole that line from someone. She had seven children. We did, and still do, look a lot alike. Our voices too.

I look at the faces in my class and wonder what’s going on in their heads. There are so many of them. I can’t read them at all. The good thing is, I’m usually wrong, especially when I imagine the worst.

When will I tell the story about the fire?

Or will I at all?

Maybe I need to think more carefully about when I need to.

Tonight was not the time.

The next morning, another class. I asked the students to write about the first movie they remember feeling something emotional. I encouraged them to describe a specific scene, but they aren’t quite ready for that kind of precision yet. I also asked them to name three objects they own that offer real insight into who they are. Two students chose stuffed animals—and for good reason. It made me want a stuffed animal.

The final question was to choose a color that matches your mood today, and another that represents your holiday break.

Yellow. Blue. Pink. One green.

I learn a lot from this exercise. Not just from what they answer, but how they answer—the extra details, the surprising accomplishments, where they’re from, where they work. Missing horseback riding. The complexity of being home with family while also enjoying being away from them. How many of them collect vinyl records. The movies they love—rom-coms and documentaries.

And again, the faces. Some expressions I can’t help but read as pure judgment. It’s a trap I fall into too easily, imagining myself at the center of everything. I am far from my students’ worlds. They have more pressing concerns. Often, it’s the students I worry most about who end up getting the most out of the class.

I did tell them about my house. It slipped out. I moved on quickly, realizing in that moment that I don’t need to hand them that weight.

January 31, 2026

NOT ENOUGH SLEEP?

When I owned a flower shop with my friend Pam, we took turns handling the weekly restaurant and hotel accounts. The best time to buy flowers, for those accounts and for the shop, was 2 a.m., when the flower market opened and all the growers were there. That was when you had the best chance of finding something unusual.

Trying to fall asleep by 7 p.m. so I wouldn’t be completely sleep-deprived was a huge challenge. I tried every natural remedy I could think of, and none of them worked. Eventually I resorted to Excedrin PM, which worked more often than not. I’m sure the real reason I couldn’t fall asleep was anxiety about getting up, or rather, not getting up because my alarm didn’t go off or I slept through it. That never happened, but I worried about it constantly.

Buying flowers for accounts meant choosing what looked good and what was available when I arrived at the market. There was no way to have a real plan. Some mornings you got incredibly lucky. The right floral elements would appear quickly: giant fig branches, beautiful lilies, unusual greenery, or some foliage or flower I’d never encountered before that added just the right color or texture. Other days, I felt like I circled the market ten times trying to find something that would work. I’d end up settling for something I wasn’t thrilled with hoping I could make an arrangement the client would like, or at least one that wouldn’t fall apart or wilt before the week was over.

We made a point of visiting our clients’ arrangements midweek to refresh them, but there were still times when we’d get a call from a restaurant manager complaining that something had died, looked bad, or was just plain ugly. Occasionally the call came the very same day we’d dropped it off.

The lack of sleep, the physical work of hauling large bunches of flowers onto heavy carts, then into my van, then again into the shop was exhausting. Hours of cleaning stems, filling buckets, and hauling water was pure drudgery and never glamorous.

One morning around 7 a.m., I arrived at a downtown restaurant and, as usual, parked illegally, something you could get away with at that hour. I went inside and took the old arrangement out of the restaurant and set it on the sidewalk next to my van. It was still fairly large, and some of the flowers looked surprisingly fresh. I carried the new arrangement inside, still unfinished, and spent about thirty minutes adjusting and adding the final flowers and foliage. When I came back outside, I saw a man wearing pajamas running down the street carrying the old arrangement in its plastic container. It was a new occurrence. I always left the old ones beside my van, and they had never been taken before. I laughed and wondered where he was going to put it.

Pam once said to me, “Sometimes I catch myself thinking, hurry up and fall asleep so you can hurry up and wake up at 1:30 a.m.” We both tried to will ourselves to sleep that way, and it never worked. The anxiety only grew. I was so afraid I wouldn’t be able to function in the real world without sleep—which, at that time, was probably true.

But that doesn’t seem to be true anymore. I don’t know if it has anything to do with moving into a new home and leaving the one I lived in longer than anywhere else, but now when I wake up and look at the clock, no matter how early it is, I’m not stressed. Maybe at this age my anxiety has shifted or maybe it’s about missing out or about how little time is left. I’d rather be awake more than sleep.

Sometimes it’s very early, 3 or 4 a.m., and I put my head back on the pillow and think. What I think about will have to be for another entry.

If the clock says 5 or later, I often decide to wake up fully. I think, check my phone, listen to The New York Times headlines, do crossword puzzles, edit a video sketch on my phone, or read. I don’t worry about being too tired to do what I need to do. That, in itself, feels like a relief. I still suspect I could use more sleep. Checking my phone, crossword puzzles aren’t more important than that. Maybe thinking is, though.

On the flipside there are hings I loved about working with flowers.

First, the beauty. Second, the beauty wrapped in newspaper.

You’d peel back the paper and there it was: dirt still clinging to the stems, thorns on the roses, leaves that needed to be stripped away to make the whole thing presentable, worthy of being bought. Beauty that required a little work, a little damage, to fully arrive.

Third, leaving the flower market as the sun was coming up. Driving over the freeway overpass, knowing the day was beginning and I had already been awake since 1:30 a.m. I made it. Now I could go back to the shop, lock the door, drink my coffee, eat my blueberry muffin, the one from the market cafe I always wished had fewer blueberries. I had plenty of time before the store opened.

I’d turn on music. Or maybe nothing. Just silence. And I would clean flowers for hours, watching the room transform from empty buckets and vases into color and smell and life. Over and over as I worked the feeling that something beautiful was being created simply by taking flowers out of newspaper, placing them in a room, and letting them be what they were made me wish I never had to open the shop. I just wanted this.

I also loved that flowers weren’t permanent. They weren’t really plants, no matter what people assumed when they asked me how to grow things (I didn’t know how to grow anything). They were cut from the ground, already on their way to death. But on the way, they were stunning.

Some stayed interesting even as they decayed. Tulips kept growing as their petals dried and curled. Lilies browned at the edges, becoming papery. Roses shriveled, bent over, almost merging with the vase they leaned against, trying not to fall completely. Those were the flowers I couldn’t display in the shop, but they fascinated me.

I was drawn to the most delicate things. Tiny bouquets of violets that would only last a day or two. I wanted them anyway. Sometimes I’d put them by the register so others could enjoy them. Sometimes I’d talk people out of buying them because I knew they wouldn’t last, and because, selfishly, I wanted them for myself.

There were giant dahlias. Camellias so perfect they looked unreal, like sea creatures. You didn’t arrange a camellia, you floated it in water. There was nothing else to do. They weren’t cheap, but I bought one anyway.

When people find out I once owned a flower shop, they always ask what my favorite flower is. I immediately say ranunculus. And then I add: really, any flower with that many layers of petals. I love the pale ones. I love the bright ones. Ranunculus have soft stems and need very little water, or they rot. They don’t last long. I learned that the hard way.

When I look back now, I mostly remember how badly I wanted to get out. I wanted to quit for three years.

We had a street stand in San Francisco and I had never been so cold. My feet were always numb. The flowers were fragile, perishable. Anything could ruin them. A dog once pissed on a whole bucket of daisies. I chased the owner down the street, asking her to pay. She resisted, then agreed when she realized they were just daisies and it would only cost her about twenty dollars. I never saw her again.

The wind was the worst. Worse than the rain. It whipped around corners, knocked buckets over, tore flowers apart. They couldn’t take it. I couldn’t take it.

The shop itself was a relief. Indoors. Legitimate. We had clients. We had to make them happy. We did a lot of weddings. I pretended I knew what I was doing, and along the way I learned how to make bouquets, arrangements, centerpieces. Weddings were stressful. The perfection, the cost, the expectations. That part wasn’t fun.

Maybe I can’t stop thinking about that time because it was about selling something never meant to last. Choosing beauty even when you know it will only be there for a few days. Buying it, bringing it home, watching it dry out and die. Doing everything you can to keep it beautiful, changing the water, cutting the stems, until there’s no return. Then you stop interfering. The water evaporates. The stems rot or dry. Petals fall and curl on the shelf.

And then you replace them.

You go back to the market. You see something new, something you’ve never seen before or something familiar and nostalgic. Pale pink spray roses, fever few, peonies, parrot tulips and ranunculas. It excites you. You bring it back. You put it near the register. You enjoy it for that brief time. Again and again.

That part never bothered me. I didn’t mind that flowers had to go when they had to go. What I hated was when they were taken too soon, by wind, rain or dogs. Or when we didn’t sell enough.

The thrill and the anxiety came together at the market: the warehouse with cement floors and metal doors, old men running stalls, often the growers themselves. Grouchy and tired from driving all night. Very few women. Twice a week I’d wheel around an enormous two-tiered cart, filling it with what I wanted to sell, what I thought might sell, and what I needed for clients and weddings. My fingernails were never clean.

I still buy flowers occasionally. I’ll be at Trader Joe’s and see ranunculus—bright orange, pale pink, sometimes a strange green. I’ll take them home and watch them fade. And I’ll wonder, briefly, if there will be more next week.